Here’s How Your Brain Orchestrates the Magic of Talking

Talking feels easy, but under the surface, your brain is running a high-stakes concert. Not one part, but a full network works together to help you speak clearly and fluently. It is not a solo act. Rather, it is a well-rehearsed symphony.

This network involves hearing, movement, memory, and self-correction. Your brain doesn’t just spit out words. It plans, listens, adjusts, and keeps everything in sync, almost like a musical performance inside your skull.

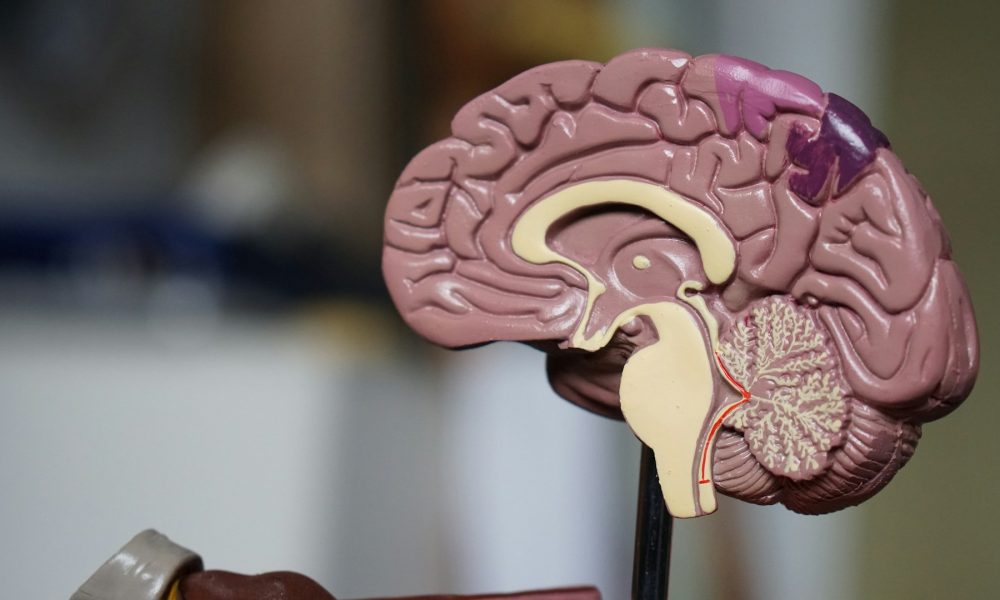

Karolina / Pexels / Before your tongue or lips move, your brain locks onto a sound. Not the movement to make that sound, but the sound itself.

So, it is like humming a tune in your head before singing out loud.

This is why you adjust your voice when you hear yourself off-key in real time. Your brain hears the mistake and automatically tweaks the sound. That is the power of sensory feedback.

The Motor System Joins the Party

Speech isn’t just about words. It is also about movement. That is where the motor system comes in. It controls the physical parts that shape your speech, like your lips, jaw, and vocal cords.

But these motor areas don’t work alone. They constantly check the sound you are producing and compare it to what you meant to say. It is a fast feedback loop that keeps your speech on track.

Area Spt, the Translator in the Middle

In the back of your left brain, there is a small region called Area Spt. It might be small, but it plays a big role. It connects what you want to say with how your muscles should move to say it.

Think of it like a conductor with a headset, taking in sound goals from the auditory system and sending precise orders to the motor crew. It also listens in and helps make real-time corrections if something sounds off.

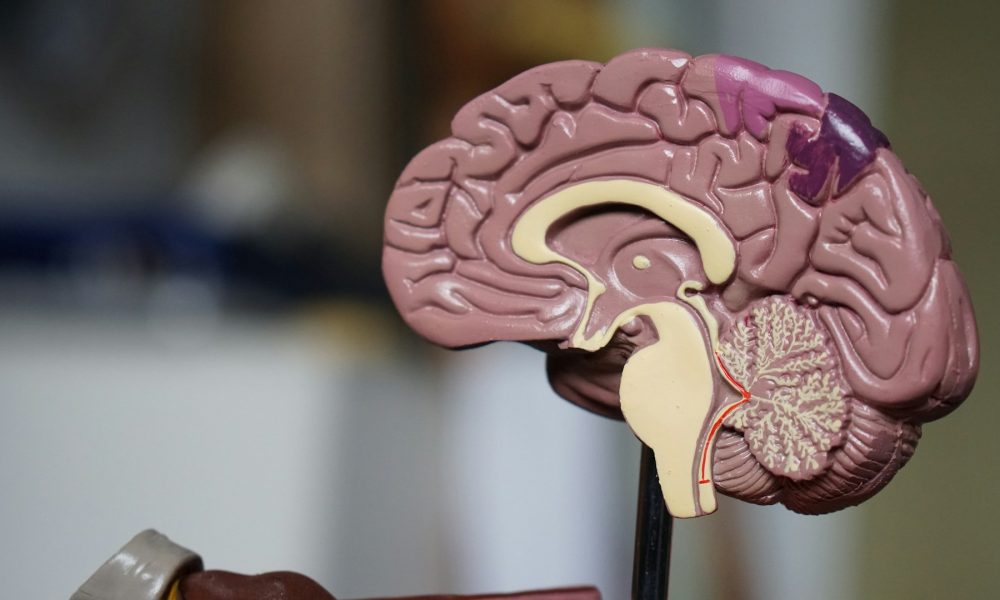

Jep / Pexels / When you decide to speak, Broca’s area jumps into action. It lives in your left frontal lobe and helps turn ideas into grammatically correct sentences.

If this area is damaged, you will still understand others but struggle to respond. Your words come out slow and broken. The orchestra knows the song but can’t play it right.

Further back in the brain sits Wernicke’s area. It helps you understand what others are saying. It makes sense of words and meaning, almost instantly.

People with Wernicke’s aphasia speak in long, flowing sentences. But the words may be random or jumbled. They can’t tell that something is wrong because their internal monitor isn’t working.

The Arcuate Fasciculus

These two areas don’t just sit next to each other and chat. They are connected by a thick bundle of nerves called the arcuate fasciculus. It is the high-speed data line between Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas.

If this cable is damaged, the brain struggles to repeat things accurately. You’ll still understand and speak freely, but repeating a sentence word-for-word becomes oddly difficult. That is conduction aphasia in action.

Once the brain finishes planning the speech, the motor cortex takes over. It is the worker bee. It sends signals to your muscles to move the right way at the right time.

You don’t need to think about which muscles to move. The motor cortex handles that. It is precise and fast, like a drummer keeping the beat.

However, speech has rhythm. And the cerebellum helps you stay in time. It sits at the back of your brain and makes sure your speech is smooth, not choppy.

It fine-tunes your pitch, volume, and pacing. If the cerebellum is off, your speech might sound robotic or slurred. You lose that natural, flowing vibe.

More inOpen Your Mind

-

`

LGBTQI+ Rights Under Threat from Federal Rollbacks

LGBTQ+ communities across the U.S. are feeling the pressure. Since January 20, 2025, a wave of federal rollbacks has hit hard,...

August 30, 2025 -

`

How Will the 2025 Lion’s Gate Portal Bless Your Zodiac Sign?

Every zodiac sign feels the ripple when the Lion’s Gate Portal swings wide open. Peaking on August 8, 2025, this cosmic...

August 22, 2025 -

`

Why the Best Way to Discover the World Is Through Street Food

Street food is the real flavor of a place. Forget fancy restaurants with white tablecloths. If you want to know what...

August 14, 2025 -

`

How Lightning Strikes Claim 320 Million Trees Annually

Lightning is striking down more than just power lines. Every year, it kills about 320 million trees worldwide, and that number...

August 7, 2025 -

`

Women of Color Build Networks of Resistance Against ICE Raids

ICE raids have shaken communities across Colorado. But women of color are fighting back with grit and precision. In cities like...

July 31, 2025 -

`

Hypnosis May Help Open Your Mind to Change & Relieve Pain, Study

Hypnosis is not mind control. It is a clinical method that puts your brain into a calm, hyper-focused state. In this...

July 25, 2025 -

`

How Good Is Street Food in South Korea?

Street food in South Korea is a way of life. You will see students grabbing skewers after class, office workers stopping...

July 17, 2025 -

`

Iconic American Vogue Editor-in-Chief Anna Wintour Steps Down After 37 Years

After 37 years at the helm of American Vogue, Anna Wintour has officially stepped down as editor-in-chief. The 75-year-old British editor...

July 10, 2025 -

`

Here’s Why Psychedelic Healing Doesn’t Need Big Pharma

Community is the heart of real psychedelic healing. Not sterile clinics. Not white lab coats. And, of course, not a billion-dollar...

July 4, 2025

You must be logged in to post a comment Login